Peter Stichbury has Suspended Disbelief

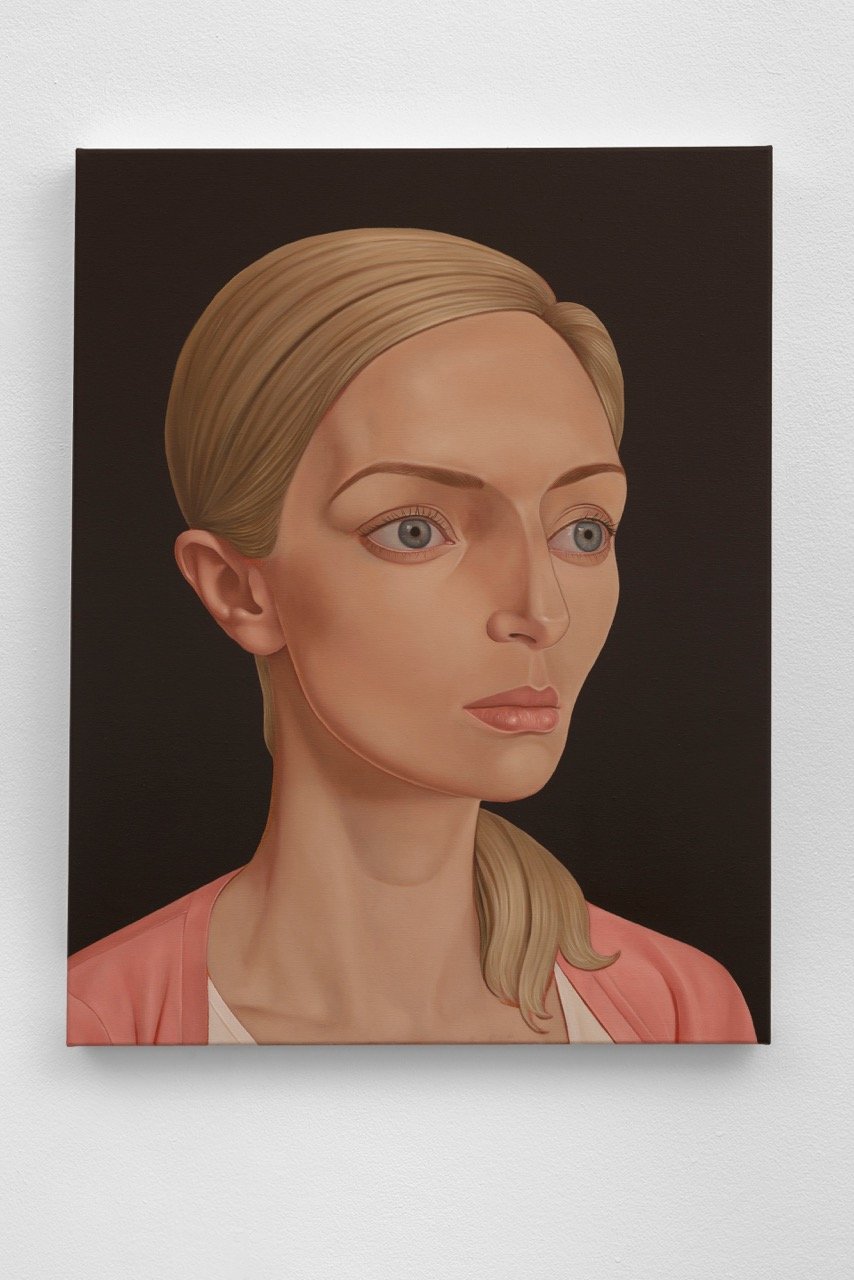

Peter Stichbury, “Vita Ventura, 1978”, 2019

“I prefer to think that mysteries are currently opaque because of how little we know, rather than because they are unanswerable”

Peter Stichbury lives and works in Auckland, New Zealand, and is known for his portraits of both real and imagined people with smooth skin, symmetrical features, and wide-set eyes.

1. Ingrid Cincala Gilbert: How did you get started in painting? What attracted you to the medium?

Peter Stichbury: A slightly cliched origin story, I’ve been painting, drawing and making things since early childhood. I still fondly remember the smell of paint in kindergarten. When I was seven I constructed a human skeleton from old chicken bones I found in the dirt on school grounds.

2. ICG: In terms of your process, I've seen some of your drawings, which are really incredible. How do you view drawing in the context of your overall practice? How do you go about the process of creating one of your paintings in general?

Peter Stichbury, “Philip Kindred”, 2019

PS: Drawing is the basic architecture, the substrate of my painting. It has an obvious directness and lack of impedance, a natural accuracy and subtlety that almost feels like an x-ray – it’s a strange process. There’s nowhere to hide, or hide errors. My drawing relies on only a few elements – tone, composition, a little variation in line, so it’s soft, light, ephemeral, an aesthetic I enjoy as a counterpoint to painting. I feel like my drawings are the quiet introvert, and my paintings are the extrovert, the full spectacle - colour, viscosity, depth. There’s a largesse in painting, a completeness in the way a successful painting can transport its audience. You set up a proposition, an externalised thought experiment for them to be drawn into, to wrestle with and perhaps untangle.

Peter Stichbury, work in process, studio, 2022

3. ICG: That’s interesting. With respect to painting, the “extroverts” as you put it, I've sensed a bit of a subtle transition in your work, with your earlier portraits, like "Swoon" or "Charity", for example, exhibiting higher dimensionality and luminosity, gloss, this giving way to a certain flatness and directness as in "Joseph Honeywell", and perhaps most recently returning once again in your most recent works to a bit more depth. Do you see this? Is it intentional or a by-product of some other goal?

Peter Stichbury, “Swoon”, 2000

Peter Stichbury, “Charity”, 2001

Peter Stichbury, “Joseph Honeywell”, 2012

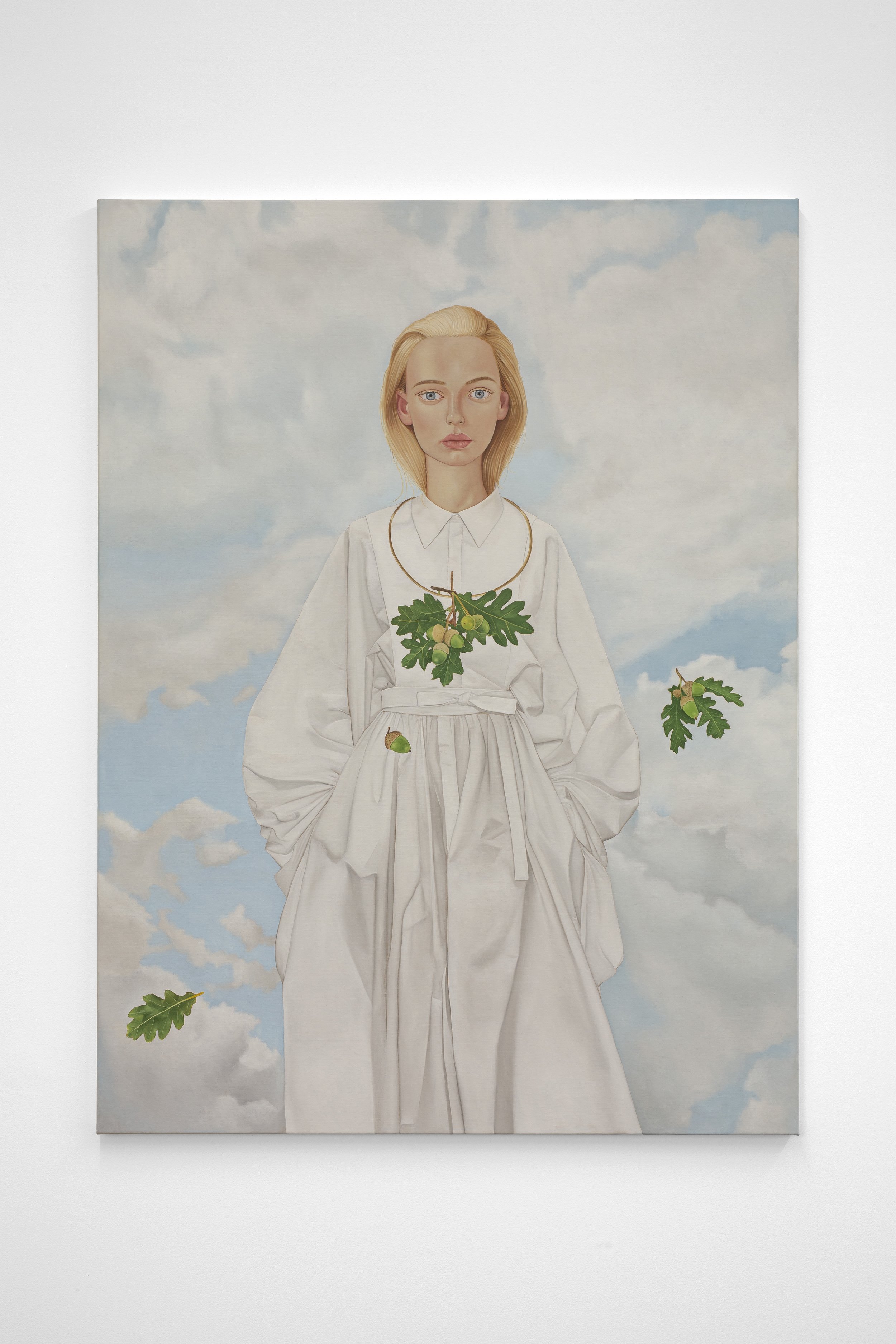

PS: The work has certainly waxed and waned in terms of dimensionality and volume. I have been influenced at times by Freud’s portraits from the late 1940s, the simplifying, flattening effect of his use of light. Currently, there are some aspects of traditionalism that I am moving back towards - some sense of naturalism, even though my work is heavily exaggerated and stylized. This supports becoming less reductive and more generous in my general articulation of subject matter. Painting the figs in Actaeon, 2022, and the funghi of Viola P. Neal, 2022, was gratifying. I spend a lot of time intellectualizing the work, so it’s been transformative to let go and revel in the poetry of rendering. Less thinking, more doing.

Peter Stichbury, “Cassandra”, 2022

4. ICG: In your exploration of the unique encounters that has been the genesis of some your works, my feeling is that you are seeking to highlight wonder and mystery as opposed to fear of the uncanny. Is that fair, and if so, why do you tend to take this path?

PS: Yes that’s fair. We know the impulse to treat the unknown as a threat is a useful biological survival adaptation, but this fear can then devolve into social restraints and stigmas; modern intellectual taboos. The Academy struggles to discuss anomalous experiences with consciousness, and politically and medically they’re difficult to broach because they’re inexplicable using the information the current scientific method can produce, and because they’re based around subjective qualitative data rather than quantitative data. But painting is the ideal context in which to address these themes. I try to resist a fear-driven or defensive stance toward mysteries that are hard to interpret within our current consensus reality. For me it’s more valuable to suspend disbelief and approach them with intellectual curiosity and imagination. I prefer to think these mysteries are currently opaque because of how little we know, rather than because they are unanswerable per se. I admire the bravery of scientists like Garry Nolan and Jacques Vallée who steadfastly confront these anomalies in their work.

5. ICG: I've read how your subjects have tended to be individuals in their 20s or 30s, who perhaps carry less baggage and tendency towards bias. I wondered if you have found corollary examples in the making of your art itself, as you yourself have matured? Do you find that your practice is substantially different than it was when you began painting?

PS: I really like that reading, but it’s not my intention. Rather than painting a particular age group, I attempt to paint people who are ageless, suspended outside time, outside our dimension perhaps. The specificity of their vital statistics is limited to the identity they are assigned, which represents an aspect of the subject I am examining at that moment.

Peter Stichbury, “Artemis” (studio), 2022

Peter Stichbury, “Artemis” (detail), 2022

Peter Stichbury, “Artemis” (detail), 2022

6. ICG: While on the surface your work has in the past focused on extraterrestrial encounters, one might say the larger focus is on the gap, or conversely the link, between the conscious and unconscious--and the fact that just because some things remain unknowable does not mean they are untrue. Are there connections you see in today's social and political discourse?

PS: I guess that’s true of all the subjects I research – the commonality of consciousness as a deeper theme. There is the relationship between societal belief and consciousness – the impact belief has on our interpretation of what consciousness is. On the one hand, Jung’s theory of a collective unconscious that connects all humans. On the other, the theory that consciousness is a construct of the social perceptual machinery, an epi-phenomenon of the brain. Debate runs high around the nature of consciousness and therefore around anomalous experiences associated with death, and around the possibility of extraterrestrial / interdimensional contact. For now we’re left with theory and the age-old debate between a materialistic and a spiritual interpretation of our existence. And of course my examination of consciousness feeds into this larger question about the nature, reason and direction of reality.

We can talk about how technology impinges upon consciousness, and transhumanistic ideas of life extension and how disturbing, and also incredible the results of that could be. I idealize people in paint, but actually manufacturing genetically disease-free humans who don’t degrade quickly, who could live hundreds or thousands of years, how does that impact us ethically at a sociopolitical level? And at the level of consciousness?

Peter Stichbury, ‘Viola P. Neal’ (studio), 2022

Peter Stichbury, ‘Viola P. Neal’ (detail), 2022

7. ICG: Portraiture has a long history of telling the broader story of the subject. In your case, the subjects are generally not famous in the mainstream sense of the word, but nonetheless I think mostly have backstories that are quite significant to your work. To what extent do you want the viewers of the work to really understand who these individuals are, and their stories, or does that miss the point?

PS: When I started looking into the personal experiences of the subjects, I felt a need to tell their accounts in a biographical way to encourage the audience to grapple with the details. Now though, the accounts have settled in so many homogenous layers that their individual identities are less important than the propositions they offer as a group: aspects of consciousness, its anatomy theoretically, and its lack of confinement to the finite physical body. Also the role of the dimensions of time and space in the human experience. Contemplations around undiscovered intelligent species and the role of consciousness in that potential future relationship. Belief systems and the function of consensus reality in shaping human interpretation of these mysteries. Philosophical thought around consciousness in the form of Platonic and Socratic theory, which is a current research interest.

My Greek heritage also offers me a rich cultural inheritance in the form of the belief system of Greek mythology, which feels very poetic and provides an antidote to the mystery and open-endedness inherent in my consideration of consciousness. Greek mythology is a closed symbolic language detailing the Ancient Greeks’ perceived sum of humanity’s elements which offers the certainty of a finite system, even though, paradoxically, it’s fictional.

Peter Stichbury, “Elysium (Tasha Malek)”, 2021

Peter Stichbury, “Jessie Sawyer, (NDE)”, 2021

Peter Stichbury, “Joseph Geraci, 1977”, 2019

8. ICG: Who are some of the artists you admire in today's contemporary art scene?

PS: So many. Neo Rauch, Tony Matelli, John Currin, Dana Schutz, Kati Heck, Kehinde Wiley, Elizabeth Peyton, Steven Shearer, Genesis Belanger. Ingres’ work feels very contemporary in its subtle stylization and lushness, and I return again and again to Freud’s Girl with a Kitten.

Peter Stichbury, “Actaeon” (detail, studio) 2022

Peter Stichbury, “Actaeon”, 2022

9. ICG: What’s next for you?

I have a solo show scheduled next year in Seoul with Gallery Baton, as well as a couple of other projects I’m excited about.

ICG: Peter thank you so much for this insight into your work and process!

***

Peter Stichbury (b. 1969, New Zealand)

Peter Stichbury received a BFA and MA in Elam School of Fine Arts, University of Auckland in 1997. He won the prestigious New Zealand art prize the Wallace Art Award in the same year. He has participated in exhibitions at the Dowse Art Museum (2022), The FLAG Art Foundation (2022), Nevada Museum of Art (2016) and Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa (2013) in New Zealand. Additional exhibitions include: ‘Human Condition’ at The Hospital, Los Angeles (2016); and ‘Artstronomy: Incursiones en el cosmos’ at La Casa Encendida, Madrid (2015). His work is represented in the collections of Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, Auckland Art Gallery, Christchurch Art Gallery, and Wallace Arts Trust in New Zealand.

Biographical information courtesy of Gallery Baton, Seoul

Arghavan Khosravi’s Precise Duality

Photos from the studio of Arghavan Khosravi

“[In] Iran, the government imposes so many restrictions and rules on us in public places...our private spaces become like havens in which we can act freely and feel more liberated. In my work, I explore the idea of contradiction as a result of these life experiences.”

Arghavan Khosravi is an Iranian-born artist based in the United States who creates hybrid works that hover in the space between sculpture and painting, and between surrealism and symbolism, often focused on issues relating to freedom and censorship with a particular focus on female protagonists.

1. Ingrid Cincala Gilbert: Your recent exhibitions have been incredibly well-received. I remember reading how early on in your painting career at school you received a tough critique, which prompted you to shift course. My guess is that positive feedback can, in a way, also bring its own pressure--perhaps a sort of pressure to keep doing the same thing. Does praise weigh fairly heavily on how you think of future directions?

Arghavan Khosravi: It is nice of you to say so. You’re absolutely right about the negative effects positive feedback can have. Sometimes positive feedback can unintentionally put artists in a box, making them a bit conservative about making bold moves, trying out new ideas and stepping out of their comfort zones or paths that have been successful. And this can sometimes happen to the artists on a subconscious level. But on the other hand artists are creative people and they can easily get bored if they repeat one idea over and over (even if that idea has received a lot of positive feedback). At least this is the way I think an artist should be in order to move forward with their creative practice(/journey) and not feel stuck.

2. ICG: The so-called Muslim travel ban was repealed, yet Iran remains on the "do-not-travel" list for US Citizens and tensions between the countries remain high. Have you had a chance to return to Iran? (If so, what was that like?)

AK: The last time I traveled home was December 2016. I returned to States exactly a week before the so-called Muslim Ban was signed. It meant that if I had stayed abroad just a week longer, I wouldn’t be able to return to the US and complete my MFA program. I haven’t been able to travel anywhere outside the US, including Iran, since. But I closely follow the events back home through my family and friends, social media and trusted news channels. What is going on back home matters to me and unfortunately things are getting worse every year (in terms of economy and the socio-political situation) which is both sad and infuriating because I believe the Iranian people and a country with so many natural resources deserve a way better government, not the incompetent theocracy that is currently in place.

3. ICG: I wanted to offer belated congratulations on your first museum exhibition, which opened in April at the Currier Museum of Art in New Hampshire. How did this exhibition come about, and what was that process like for you?

AK: Thank you! For me it was an incredible experience. It was my first museum solo exhibition and it was the first time that a large number of my paintings (23) spanning three years were exhibited. The museum also published a catalog accompanying the exhibition, sort of a monograph, which was also a first for me. I also did a residency at the museum which was a great experience to engage with the local community about the show. The curator of the exhibition, Samantha Cataldo, had come across my work at the Spring Break Art fair in NYC back in 2019 (It was the first art fair I participated in after I graduated in 2018). We had two studio visits afterwards. She mentioned that she had shown my work to her colleagues at the museum and they were also onboard to do something together in the future but nothing was confirmed or formalized yet. Then the pandemic happened and everything was on pause for a while. It was during the quarantine that Samantha and I had our next meetings via Zoom and started planning about the show and the residency. It was an amazing experience all along the way.

4. ICG: Your artworks are constructive, and often combine what I'll call "real" elements with those that are depicted. A straightforward example is the red cords that appear in some of your works, which sometimes are string and other times painted. Similarly three-dimensionality, or the effect of layering, is sometimes painted while other times built up out of the actual canvas itself. How do those decisions of when to depict versus when to use the "real" thing get made?

"The Black Pool"

Acrylic on cotton canvas over wood panels,found object, glitter, elastic cord, 60 × 64 × 16 in, 2022

AK: Your observation is right. I am interested in constructing a 3D space or using a found object and then juxtapose it with a 2D painted space or object which looks three dimensional. I like how this juxtaposition invites the viewer to take a closer look and spend more time with the piece to figure out which parts are real and which parts are sort of trompe l'oeil. Beside that, one of the main concepts in most of my paintings is the idea of contradiction. I explore this idea of contradiction both in terms of the subject matter and concepts I have in my work (by juxtaposing imagery from Eastern vs. Western, historic vs. contemporary or religious vs. secular contexts) and in terms of the paintings’ materiality and one of the ways to achieve that is by juxtaposing the real object and the painted one.

5. ICG: Much has been made of the duality of your work and in particular how that relates to the experience of being an Iranian woman, especially one who now lives in the US. As a person coming from that culture to the culture here in the US, have you observed any similar dualities within American society?

AK: We encounter dualities in Iran primarily due to the distinct separation between our private and public spaces. This separation exists in every corner of the world, however in Iran, the government imposes so many restrictions and rules on us in public places (for example, the compulsory hijab) that, on the other hand, our private spaces become like havens in which we can act freely and feel more liberated. In my work, I explore the idea of contradiction as a result of these life experiences. As I have just explained, I have not experienced duality in the sense that I just described in the US. In spite of racial and cultural differences, polarizations, and divergences within the US society, they are not comparable to the duality imposed by the Iranian government.

6. ICG: From what I understand, the Iranian people are creative, but the arts are tightly controlled. Does your work have an audience in Iran? Would you like to exhibit work there someday, if it were possible?

AK: You are right. In Iran there are a lot of censorship and boundaries that are dictated on the Iranian people including the artists. And sometimes these limitations push the artist to find creative ways to circumvent those restrictions (I should add that I hope there will come a time when the artists’ creativity will only focus on their freedom of expression, not finding ways to make their voices being heard without getting in trouble). Thanks to social media I can share my work with the Iranian audience and the largest number of my viewers on social media are in Iran. I am very glad that we have this virtual window to communicate. Because my work is reflecting on my life experiences in Iran and the Iranian audience is the most familiar with the context the paintings are coming from. It is my ambition to one day be able to exhibit my work in Iran without being forced to give in to those boundaries.

Photos from the studio of Arghavan Khosravi

Photos from the studio of Arghavan Khosravi

7. ICG: Your work straddles surrealism and symbolism, and while it is clearly unique I think there are influences and connections to other artists that are present for the viewer to uncover. Who are the artists you looked up to as your practice was developing?

AK: It’s a hard question because it’s a very long list. I always have an eye on different artists from different genres and eras. From Ancient Roman Greek artists to Renaissance painters to Persian miniature painters to contemporary artists. I realized that I sometimes learn and get inspired the most from artists who make works that are extremely different from what I do.

8. ICG: Your paintings seem to me almost scientific in their execution and precision, but still immensely creative. I might even go so far as to describe them as beautifully engineered. Your father was an architect, and you yourself were trained in mathematics before moving into art. Do you feel this need for precision in your work? Do you allow yourself "false starts" or "happy accidents"?

Photos from the studio of Arghavan Khosravi

AK: The way I approach painting is very controlled and preplanned. During the sketching (/planning) phase I am the most spontaneous and creative and try out different ideas and compositions. That’s the time I allow myself for—as you beautifully phrased it—“false starts” and “happy accidents”. Once I come up with a sketch that I’m quite satisfied with, the painting (/execution) phase begins. That’s when everything is very controlled and precise, and there is not much room for accidents. Because of the way I paint, which is an additive process, if I make a mistake or change my mind, there’s almost no way to fix it. Especially when I’m working on shaped panels or textiles, I should have a clear idea of what I’m going to paint within that shape and also which parts of the textile I want to leave exposed.

But still I leave some room to make some changes or add to my initial sketch (which usually doesn’t exceed 10 percent of the whole process). I should mention that I started painting from the other end of the spectrum, pouring paint on canvas and making more process-based paintings but I didn’t find both the process and result satisfying. The feedback I received wasn’t very pleasant either (part of the harsh critiques you mentioned in your first question were about these series). It took me a while until I could develop my own creative process which is evolving ever since. And I think this mode of painting is coming more from my graphic design background rather than mathematics (I studied graphic design in college and used to work as a commercial graphic designer for 10 years, before coming to the US to study painting).

Photos from the studio of Arghavan Khosravi

9. ICG: I'm curious about your studio. How do you like to work? Do you work with music, in silence? Are you most productive at a certain time of day?

AK: I always work on a table rather than on a wall or easel. Because of the way I use acrylic paint which is often watered down, and my precise approach. Most of the time I listen to audiobooks or podcasts while I’m painting. I also sometimes watch TV series on my iPad. Although it might seem impossible to have your eye on both the screen and the painting surface, I usually pick programs that I can follow the story by mostly listening to the dialogue and having a glimpse to the screen every once in a while. This combination of watching/listening and painting is the most enjoyable when I am working on parts of the painting that have a lot of details and repeated elements (like the landscape or the battlefield scenes) that are very time consuming. In this way I find myself more patient working on all those details because my mind is occupied with something else parallel to the act of painting.

10. ICG: Persian Miniature painting, which your work clearly references, has a history of being linked to royalty or other traditional systems of rule. It also, from a more direct compositional standpoint, offers some very interesting and ambiguous ways to depict space. How do you feel your works relate to this painting style?

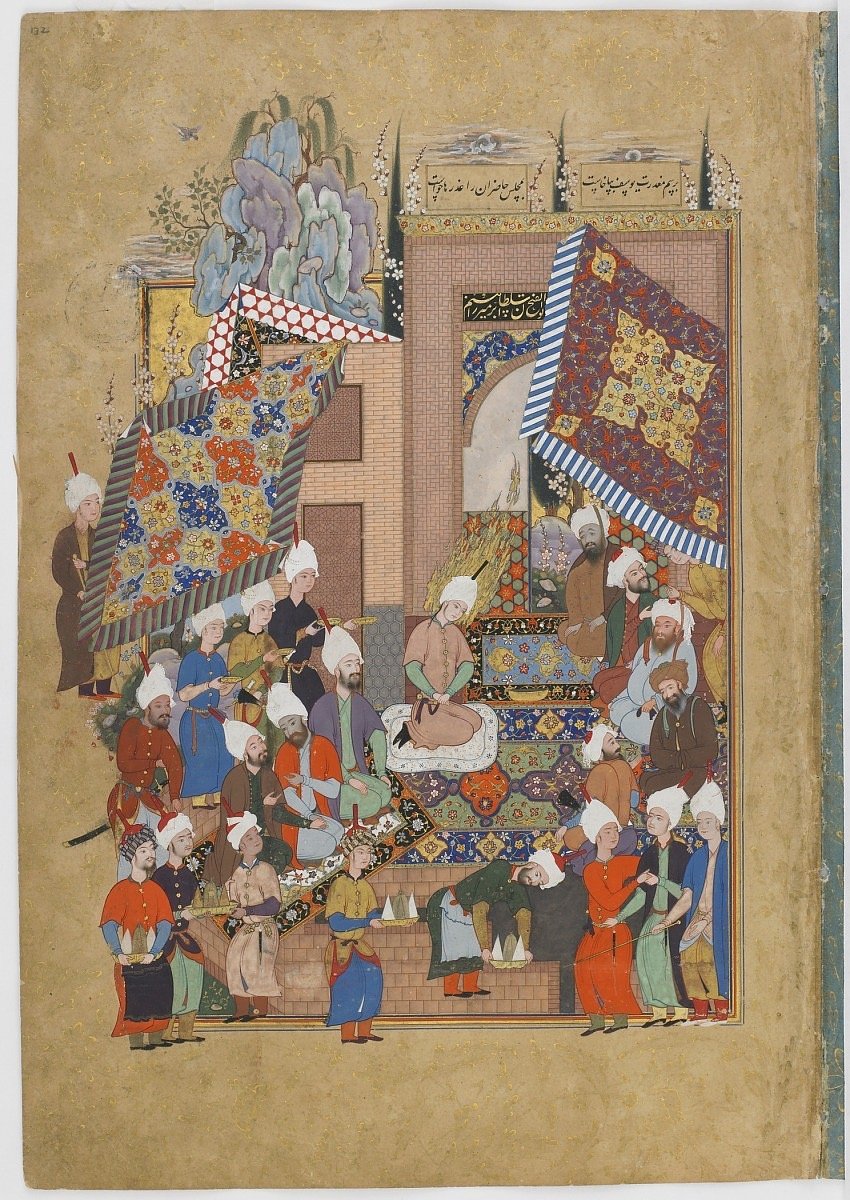

Folio from a Haft Awrang (Seven Thrones) by Jami (d.1492); recto: Yusuf gives a royal banquet in honor of his marriage

AK: One of the aspects of Persian miniature paintings that always fascinate me is their lack of perspectival depth and the way their scenes unfold across a single picture plane. I like to appropriate these compressed, compartmentalized scenes and build my own narrative upon this structure. I place figures that are rendered realistically (and are often out of proportion compared to their surroundings) in that unreal space. This contrast creates some sense of displacement that can be interpreted metaphorically too. Earlier, I talked about the idea of contradiction as one of the main concepts in my work and this is another example of that.

Besides that, the idea of shaped panels in my work came from miniature paintings too. These works were almost always made to be part of a book. The artists had always to picture plains to work with. One the paper and one the other frame which they painted inside that paper. There are some moments in those works that some elements of the painting grow out of that frame. It could be parts of the building, landscapes or even figures. I was very interested in this idea and thought of a way to translate it into my own painting which led me to shaped panels.

"The Touch"

Acrylic on cotton canvas over shaped wood panel, 36 × 31 1/2 × 1 1/2 in, 2019

ICG: Arghavan, thank you so much for your time, and for your art!

***

Arghavan Khosravi, Portrait by Hossein Fatemi

Arghavan Khosravi (b. 1984, Iran)

Arghavan Khosravi earned an MFA in painting from the Rhode Island School of Design after completing the studio art program at Brandeis University. Khosravi previously earned a BFA in Graphic Design from Tehran Azad University and an MFA in Illustration from the University of Tehran. Khosravi has participated in numerous group exhibitions, at venues such as The Currier Museum of Art Manchester, NH; The Museum of Contemporary Art, Yinchuan, China; Newport Art Museum, Newport, RI; and Provincetown Art Association and Museum, MA; among others. Khosravi’s residencies include The Currier Museum of Art, Manchester, NH; The Fine Arts Work Center, Provincetown, MA; the Studios at MassMoCA, North Adams, MA; Monson Arts, Monson, ME; and Residency Unlimited, Brooklyn, NY. Khosravi is a 2019 recipient of the Joan Mitchell Foundation’s Painters & Sculptors Grant and a 2017-8 recipient of the Walter Feldman Fellowship. The artist’s work belongs to the collections of Those Rose Art Museum, The PAFA Museum, The Newport Art Museum and The Rhode Island School of Design Museum.

Biographical information courtesy König Galerie, Berlin

Laura Berger is in a Mood

Photos from the studio of Laura Berger. Photos courtesy of the artist

“I think of my paintings as being feeling-based—being born out of that place and primarily focused on conveying mood or emotion.”

Laura Berger is an artist based in Chicago, whose work explores self-understanding on levels both physical and spiritual. Laura’s most recent exhibition “Soft Bound” at Eve Leibe Gallery in London closed on June 30th.

1. Ingrid Cincala Gilbert: To what extent do you think your art is personal, and to what extent universal?

Laura Berger: It's definitely a combination of both. The themes I'm choosing to focus on are pretty universal, but they're all concepts that have a deep resonance for me personally. Since all of these general ideas get filtered through my own background, experiences, and whatever my current emotional landscape is, that probably inevitably pushes them a bit more towards the personal.

2. ICG: So it sounds like it is a bit of push and pull, but that perhaps your emotions are the key driver?

LB: Yes, I do think of my paintings as being feeling-based—being born out of that place and primarily focused on conveying mood or emotion.

3. ICG: Some of your most recent work seems to me like landscapes formed out of complex intertwining of human bodies and forms. Is this something you think about when composing the paintings? To what extent do you feel like nature informs your work?

LB: It's interesting because I feel like a lot of what I'm making is responding to a sense of longing that I have for different things, and nature is one of them. Connection is another. I feel a larger need for nature in my life than I'm able to have currently, living in a city and hustling quite a bit to stay afloat. So it may be that these ideas come from that place, and one of the themes I'm exploring a lot is our human relationship with the natural world. Creating those formations of figures that you mentioned started kind of accidentally and is really meditative for me - drawing one sort of lounging figure and then trying to add another, and another...it's enjoyable because it becomes almost like a puzzle to solve, like how can I make them all fit together and end up with something that's both pleasing to the eye and also functional in terms of narrative and composition?

4. ICG: Lately you've been working in oil rather than other media. Has moving to oil changed the way you execute your ideas? From the perspective of the slower drying time, do you make use of the flexibility that the material can provide?

LB: Yes, the medium shift has definitely had a huge impact on my work in many ways. Oil paint is so amazing in its versatility—there are so many different ways you can apply it and the effects you can achieve are pretty infinite; it's both exciting and overwhelming to me as a self-taught artist to think about how much there is for me to discover. I'm learning so much as I work, and I wish I had lots of extra time to just experiment. I work in layers now, so my process is much slower, and I usually have anywhere between 2-4 paintings in progress at a time. Using oils has opened up a lot of possibilities for me conceptually too—for example, the ability to create different light effects or transparencies, which are things I've been incorporating a lot lately, is much more achievable. I also get a lot out of the physical sensation of working with the paint; it's so tactile and has such an organic feel to it which helps me to feel more connected to the medium itself as I work, and it's just really enjoyable to use.

5. ICG: Color seems to play a particularly important role in your paintings. To me the palette is often subtle, perhaps drawing from nature, as opposed to a more discordant mix of colors that might be more akin to an urban experience. Talk a little about how you view the use of color in your practice.

LB: Working with color is my favorite part of painting; it's probably what initially drew me to it for its therapeutic qualities. It's really such an incredible thing how we can both tap into our feelings and convey a mood solely through color combinations alone. In terms of the color choices, they're mostly just intuitive for me—using what feels right in the moment, both aesthetically and emotionally. Maybe since a lot of the themes I'm working with are coming from a sort of core or internal place it makes more sense if the colors lean more towards natural tones, but this isn't something I tend to think about consciously—I think it's just what I'm drawn to.

6. ICG: One of the things that some have pointed to concerning the pandemic was a sort of forced reconsideration of how we are going about things, as individuals and as a society, and where our energies should really be focused. While the pandemic may not be over for many, we seem to be emerging from the darkest period at least and for the moment entering into a new, somewhat more normal, phase. I'm wondering what lessons you took from the pandemic, and specifically if (and how) it impacted your work?

LB: Personally I feel like I'm very much still on the whole transformational journey right now with the effects of these years still unfolding...especially here in the U.S. where the pandemic has intertwined with so much political and social upheaval. There are events happening daily here in our news cycle that are just far too intense to process; it's overwhelming. I've gone through many phases and every day is different so it feels a bit difficult to pin down the effects as I still feel quite in the midst of it all; mostly it feels like the before times were some sort of strange dream and I'm still finding my footing within this new era. But certainly all of those complex feelings and experiences get rolled into creative output. I mentioned previously that I switched mediums at the beginning of the pandemic and I feel like I'm only just now beginning to tap into a bit of flow with it, so overall it has felt like a super long transitional period and I'm not really sure what's next for me. I do feel like the uncertainty is becoming the norm now, so I hope to continue to become more resilient and I hope that learning to adapt to constant uncertainty could help me to paint more freely as well.

7. ICG: Laura I know you have a love of travel. Have you been able to start traveling again, now that restrictions have been lightened? Are you approaching travel differently now?

LB: I do love traveling and I've missed it very much, for me there's nothing more inspiring than visiting a new place! In the past couple of years I've been to different areas in Mexico a few times, but I haven't been able to do much beyond that. It's been a really busy year for me with work so I've mostly been locked in my studio! I'm hoping to be able to get away for a bit in the coming winter. But yes, the current inflation and climate concerns are certainly having an impact on the way I'm thinking about traveling, too.

8. ICG: What's next for you?

LB: I have solo shows coming up this year at Stephanie Chefas Projects in Portland, Oregon and Hashimoto Contemporary in L.A., as well as a couple of group exhibitions that I'm looking forward to.

ICG: Thank you for providing us with some insight into your work Laura!

***

Photo courtesy of the artist. Biographical information via Eve Leibe Gallery.

Laura Berger

Centered around themes of interdependence and self-understanding, Laura Berger’s images focus on figurative archetypes, intuitive color palettes and dreamlike minimalistic environments. Initially approaching painting as a therapeutic practice, her work serves as a means through which to explore and articulate experiences and memories that feel just out of reach, that exist on a more spiritual or emotional plane. Laura has exhibited her work at numerous galleries across the US and abroad.

Anna Weyant’s Beautiful Aggression

Photos in the studio of Anna Weyant in New York. Photo credit: Cincala Art

“A lot of the work in the show focuses on fear, desperation, isolation and aggression.”

Anna Weyant is a Calgary-born, New York City-based figurative artist who paints often autobiographical narrative scenes that draw inspiration from a range of art historical precedents while injecting and contemporary, unique spirit.

1. Ingrid Cincala Gilbert: Tell me about your process. How do you begin?

Anna Weyant: I make a series of sketches. The image can change as I develop the narrative, so the sketches aren’t always fully rendered.

2. ICG: Do you paint one work at a time or do you sometimes have a number on the go?

AW: I can only focus on one at a time, though I usually have a few in-progress paintings lying around.

3. ICG: Which contemporary artists working today would you say have been an inspiration? Have they influenced you in a particular way?

AW: “The Entertainer” by Jamian Juliano-Villani is one of my favorite paintings. I also adore Ellen Berkenblit’s portraits of screaming women. This isn’t contemporary but there’s a Frans Hals painting, "Two Laughing Boys with a Mug of Beer," that I can’t separate from Berkenblit’s work. One of the boys in the image, the boy on the left who isn’t the focus of the painting, is open-mouthed in a disturbing way. It’s an expression close to a smile but it’s joyless.

4. ICG: How have you managed the lockdowns? Did it alter the way you work?

AW: I work alone and out of my apartment, so my studio practice doesn’t look very different. But the lockdown has probably added an emotional weight to what I’ve been making.

5. ICG: Your first solo exhibition was in 2019 at 56 Henry in New York, next up is your second solo show, this time at Blum and Poe in Los Angeles — is there a prevalent theme to this new show?

AW: The exhibition is named after one particular painting, titled “Loose Screw,” which depicts a lone woman at a bar laughing. The figure in the painting looks somewhat desperate, lonely and unhinged. A lot of the work in the show focuses on fear, desperation, isolation and aggression.

ICG: Thank you so much for your time Anna, and for the wonderful studio visit!

Photo credit: Cincala Art

Anna Weyant (b. 1995, Calgary, Canada)

Anna Weyant’s figurative paintings and still lifes bring to mind childhood bedtime stories and nursery rhymes. Both familiar and ominous, Weyant's versions of these stories feature young female characters trapped in tragicomic narratives. Their stories take unexpected twists at each turn, illustrating complex personalities and attitudes, and an awareness of life's irony. Often autobiographical, Weyant’s characters are amusing and endearing, though simultaneously moody and dark. Her palette prioritizes dark greens and yellows, neutral hues that highlight juxtapositions of humor and solemnity, rebellion and repression. She references an eclectic range of art historical influences, from seventeenth-century Dutch painters like Gerrit van Honthorst to contemporary artists Lisa Yuskavage and Will Cotton, and pop culture references such as New Yorker cartoons, Bugs Bunny, and the Grinch.

Weyant received her BFA from Rhode Island School of Design, Providence, RI. Weyant’s work was the subject of the solo exhibition Welcome to the Dollhouse at 56 Henry, New York, NY (2019). Her work has been featured in group exhibitions, including Life Still, C L E A R I N G, New York, NY (2020); Sit Still, Anna Zorina Gallery, New York, NY (2020); Humanmakes, Recharge Foundation, Singapore (2020); Historicity, Ochi Projects, Los Angeles, CA (2019); Of Pursism, Nina Johnson Gallery, Miami, FL (2018); and Circles without Breaks, Local Projects, Long Island City, NY (2017).

Biographical information courtesy Blum and Poe, New York

***

Liz Deschenes’ Active Surfaces

Tilt / Swing (360° field of vision, version 1), 2009. Exhibition: Liz Deschenes, ICA Boston (June 29 - October 16, 2016). Photos courtesy the artist and Miguel Abreau Gallery, New York.

“I respond to what’s happening on the surface of the works, and adjust accordingly.”

Liz Deschenes is an artist who lives and works in New York. Deschenes’ work has been noted for its exploration of representation and abstraction in photography, especially as it relates to the permanence and impermanence of experience and process. CA had an opportunity recently to discuss the work with the artist.

1. Ingrid Cincala Gilbert: Your work is often referred to as non-representational photography, but to my mind it is quite clearly not reductionist or pure in the sense of what we often think of as minimalist. Can you speak to this categorization of non-representational photography with respect to your work, and specifically how you seek to reveal, conceal or otherwise address the possibilities within the medium of photography? How do you see your work placed within the broader arc of art history?

Liz Deschenes: If it’s non-representational it’s also at times representational—from some of the green screens and black and white screens, to the Moires to the silver photograms—there is recognizable content. Sometimes the content is a material condition and, sometimes, it’s more direct—an image of a screen is photographed and printed to reveal the pixels, the warp, the weave. A fellow artist recently said the work was structuralist—I think the work hovers around these distinct areas of categorization. Suffice it to say, I don’t want the work to be so easy to classify. It’s not minimalism, conceptualism or abstraction. But, at times, it borrows from and nods to them all.

Moiré, 2007; Green Screen #5 ed. 1/5, 2001; Elevation #1 - #7, 1997. Exhibition: Liz Deschenes, ICA Boston (June 29 - October 16, 2016). Photos courtesy the artist and Miguel Abreau Gallery, New York.

Gallery 7, 2014. Exhibition: Liz Deschenes, ICA Boston (June 29 - October 16, 2016). Photos courtesy the artist and Miguel Abreau Gallery, New York.

2. ICG: I love the element of surprise and chance that permeates your work, and I think I am particularly drawn to your photograms at least partially for this reason. As photographs made without the use of a camera, I suppose the first implication here is that capturing images, at least in the traditional representational sense of photography, is not the goal. But when reading about your process I was struck by the importance of the variables that are welcomed, and quite literally absorbed, into the work. Things like temperature, humidity levels, and the ambient light from natural sources as well as the built environments all come into play and leave their unique, non-repeatable marks. But this is not something you explicitly seek to control or stage, like, say, in a traditional photographic portrait. Can you speak more to this idea of chance vs intention, and how your process relies on both?

LD: They are always in conversation—intent and chance. I think that there’s probably a lot more control in the procedures than I may have articulated in previous interviews. I’m very experienced and comfortable with Photographic papers and chemicals; I’d say that the 30 plus years of making photographic prints allows me to play with chance in ways that are probably less about “experiment,” and more about knowing to a certain degree what variables will manifest in compelling and new-found results. I respond to what’s happening on the surface of the works, and adjust accordingly. That said, there are some situations that are extreme—like high heat and humidity—these can be difficult to replicate, so I don’t try to duplicate previous sessions. Instead I find new sets of variables that can result in all unfamiliar marks, surfaces and tones.

3. ICG: In an interview with Jonas Storsve in 1991, the musician John Cage, when speaking about his collaborations with the dance choreographer, Merce Cunningham, related the pair’s working style as less associated with an “object” that has clear boundaries from the onset, but rather a “style” akin to unpredictable weather patterns, where difficulty arises in precisely pinpointing when one thing (the music) starts and another (the dance) ends. Accordingly, the two artists never began a project with a pure idea but rather provided conditions within which each individual art form could interact, with the goal being the creation of a third thing: something new and unpredictable. This interplay reminds me of the attention you pay to the exhibition of your work—the way that work inhabits and responds to a space (and sometimes changes itself throughout the course of an exhibition), and the way that viewers experience both the work through time. It seems the intention here is to reveal something beyond the “object.” One clear example is your exhibition at the Secession in Vienna in 2013, where procession played such an important role. Can you speak to the idea of the parcour, and how the art relies on (or is changed by) the path of movement of the viewer?

LD: In almost every solo outing, I determine the placement of the walls, and in the case of Secession, the rerouted entrance to the space. The basement of Secession is usually entered from stairs or an elevator from the main gallery upstairs, and the viewer passively enters a not-so-coherent schema of three spaces. I altered the approach to these galleries by opening up a side entrance that is usually only accessible, and reserved for, the friends of Secession. By doing so, I have accomplished two important criteria for the work: conscious (and not passive engagement) and viewing through a portal now made available to everyone, and not the select few. It also made the sequence of the spaces much more logical, opening up possibilities for movement and autonomy by and for the viewer.

Exhibition: Liz Deschenes (December 7, 2012 - February 10, 2013). Secession, Vienna. Photos courtesy the artist and Miguel Abreau Gallery, New York.

Stereograph 1-16, 2012. Exhibition: Liz Deschenes (December 7, 2012 - February 10, 2013). Secession, Vienna. Photos courtesy the artist and Miguel Abreau Gallery, New York.

Green Screen #4, 2001/2016. Exhibition: Liz Deschenes, ICA Boston (June 29 - October 16, 2016). Photos courtesy the artist and Miguel Abreau Gallery, New York.

Gallery 4.1.1, 2015.Exhibition: Liz Deschenes, ICA Boston (June 29 - October 16, 2016). Photos courtesy the artist and Miguel Abreau Gallery, New York.

4. ICG: How work is produced (i.e., its technique or technology), has historically been an important component of all art, and indeed in some cases a defining element of an entire movement, as in (for example) the action and stain painters of the 1950s. Photography, however, was an art form impossible without leveraging more complex and generally less immediate science. As such it has been particularly defined over its relatively short history by technological advances. Today, however, with the move to digital photography, one could argue that layers of process and production have been denied, supplanted by the immediacy of speed and by an emphasis on post-production. What role do you think technology has in your work, and what can slowness reveal?

LD: In thinking about this question I was reminded first of a paragraph written by Carter Mull about my work, which I think is relevant. With his permission I’ve re-presented the excerpt below.

“The obsolete, artisanal, and focused technologies of black-and-white printing are employed in Liz Deschenes’s silver monochromes. These works etch a line in time, raising questions with philosophical import that are only intensified by the hypertrophic backdrop of the global art industry. Standing in the tiled-floor space of an Orchard Street storefront commercial gallery (once a former monastery), I wonder if these silver monochrome objects were exposed using moonlight from a Vermont night. Far and away from the maddening apparatus that is the city’s youth-consuming engine, these pieces reflect quietude. Their silvery color—not color, actually, as that’s something different—a language culled from painting. The silver is a dropout. It pulls itself away from the formation of a legible image and moves to the register of process. What appears as color is the accrual of silver onto the surface of a sheet of emulsified, charged silver gelatin fiber paper. The halidation of the paper is what makes it seem so material. These are the substances of an older era—a group of technologies once employed to print the day’s news photos for the press. Now the same basic matter is used in the production of an object with specific structural properties. Although these works are made with multiple processes (printing, mounting, and framing to name only a few), the primary concern is the activation of the page with silver via artisanal photographic chemistry. When we see the surface, we see the production by which the work is made.”

Moiré, 2009. Exhibition: Liz Deschenes, ICA Boston (June 29 - October 16, 2016). Photos courtesy the artist and Miguel Abreau Gallery, New York.

Bracket #7, 2014. Green Screen #5, 2001. Exhibition: Liz Deschenes, ICA Boston (June 29 - October 16, 2016). Photos courtesy the artist and Miguel Abreau Gallery, New York.

5. ICG: Many of your photograms intentionally oxidize over time. Because multiple in-person visits would ideally be needed to appreciate their mutability, a certain complexity of interpretation, and criticism, is introduced. In essence, one person’s experience of a particular work could be quite different than another’s—not just because the viewers are different, but also because the work itself is changing. Could you discuss the nature of change and your thoughts on how these works ought to be seen? What role does time play in your work, from creation through the viewing process? When do you consider a work like this to be finished?

LD: Many of my concerns are spatial, material and experimental. I research the beginnings of inventions, failures, overlaps, and the shared desire to make certain discoveries come to light. The work is never really finished, as I often make plans to reconfigure work from previous installations. A recent example of this was the survey exhibition “Timelines” at ICA Boston, which I later took the same work and reconfigured, with two photographs added on, in order to complete a circle at Art Unlimited this past spring in Basel, Switzerland.

Timelines, 2016. Exhibition: Liz Deschenes, ICA Boston (June 29 - October 16, 2016). Photos courtesy the artist and Miguel Abreau Gallery, New York.

Timelines, 2016. Exhibition: Art Basel, 2017. Photos courtesy the artist and Miguel Abreau Gallery, New York.

6. ICG: Your work has been compared to Sherrie Levine’s and Sarah Charlesworth’s in terms of using photography to question the photographic representation in our culture. Could you speak a bit about how you view your work in relation to that by the Pictures Generation artists?

LD: Every generation has a debt to clear with the previous one. In my case, studying art in the 80’s, it become clear that the work of the “pictures artists,”—the not-so-correctly-named artists using photography, grouped by an exhibition many of them were not even in—what they were doing was very different, in that they were critical of accepting photography’s conventions, gender biases and proscribed roles. Their work asserted a forcefulness and intelligence that had to be reckoned with.

Since coming to NY, I have taught with Sarah, exhibited with Sherrie’s work and, post her sudden and too-early death, I participated in a panel discussion about Sarah’s work and curated a solo exhibition of Sarah’s work in Paris. Tragically, she did not get to do that while she was alive. Like them, I am interested in using photography to upend traditional notions of image making. Because the “pictures generation” has been so eloquent and successful in critiquing the failures of modernism and lack of inclusion, they have opened up other possibilities, for me, and my generation of artists, to tackle a distinct set of questions.

ICG: Liz, thank you so much.

***

Photo courtesy of the artist.

Liz Deschenes (b. 1966, Boston)

Liz Deschenes graduated from the Rhode Island School of Design in 1988. She teaches at Bennington College and is a visiting artist at Columbia University’s School of Visual Arts and Yale University. Her work is held in the permanent collections of the Centre Pompidou, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, theSolomon R. Guggenheim Museum, the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Museum of Modern Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Walker Art Center, The Art Institute of Chicago, ICA/Boston, the CCS Bard Hessel Museum of Art, the Milwaukee Art Museum, the Corcoran Museum of Art, and the Hirschhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden. She was the recipient of the 2014 Rappaport Prize. Deschenes has recently presented her work in a series of two-person exhibitions with Sol LeWitt at Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco (2017), Miguel Abreu Gallery and Paula Cooper Gallery, New York (both 2016). Her work was the subject of a 2016 survey exhibition at the ICA/Boston. In 2015, Deschenes presented solo exhibitions at MASS MoCA and the Walker Art Center, and was included in group exhibitions at the Whitney Museum of American Art, Musee d’Art Moderne, the Centre Pompidou, and Extra City Kunsthal in Antwerp. In 2014, her work was featured in Sites of Reason: A Selection of Recent Acquisitions at the Museum of Modern Art and in What Is a Photograph? (International Center for Photography, New York). In 2013, she exhibited new work in tandem solo exhibitions at Campoli Presti (Paris and London), and group exhibitions at the Museum of Modern Art and the Fotomuseum Winterthur, among others. In 2012, she was included in the Whitney Biennial and had a one-person exhibition at the Secession in Vienna and a two-person exhibition at The Art Institute of Chicago that she co-curated with Florian Pumhösl and Matthew Witkovsky. Previously, her work has also been exhibited at the CCS Bard Hessel Museum, the Aspen Art Museum, Klosterfelde (Berlin), the Walker Art Center, the Langen Foundation (Düsseldorf), the Tate Liverpool, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Biographical information courtesy Miguel Abreu Gallery, New York